|

The

Akhal-Teke

Born to challenge the wind of the desert! |

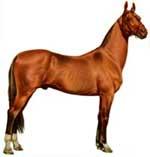

Divine horses, equine aristocrats, fabled steeds, effulgent diamonds - such flowery epithets have been lavished upon that unique equine breed - the Akhal-Teke. Prized by Alexander the Great, Darius the Great, Genghis Khan, Roman emperors, Marco Polo, and many others, the Akhal-Tekes have served people for over 3,000 years.

Absolutely everything about this horse is unique, outlandish and stunning. It is the most ancient breed on earth. It is one of the most beautiful, elegant and proud horses in the world. Its endurance and resistance to heat are second to none.

Turkmenistan’s national emblem featuring the Akhal-Teke |

The Akhal-Tekes come

from the Kara-Kum Desert in Turkmenia. It is a place for the toughest

people and equines. The Turkmens would never have survived without the Akhal-Teke, and vice versa. Turkmens were the first desert people to produce a horse ideal for the environment. |

Today’s Akhal-Teke is a race, sports

and endurance horse, and a riveting circus performer. Smaller Akhal-Tekes

make great Western horses because of their quickness.

The Akhal-Teke takes its name from a Turmenian

tribe Teke that lives at the Akhal oasis. It is one of the

most distinctive horses in the world. Nearly everything about it is exotic

and outlandish. Experience of Russians, themselves a race with an Asiatic

mentality, shows that some Westerners have a difficulty perceiving the

unusual nature of everything about that fiery steed born to challenge

the wind of the desert and catch the fancy of Alexander the Great and

a long line of historic figures of Greece, Rome, and the Levant.

But the horse is not exactly meant to grace

with his presence fancy air-conditioned stables, and to be fed in a way

that suits German or Swedish warmbloods. Russians will never understand

the European possessors of ex-kings of the desert who proudly parade in

front of them overfed underexercised creatures hot-ready for Hanover or

Holstiner show rings.

Conformation

The Akhal-Teke’s exterior makes it very different

from other breeds. Some authorities maintain that the Akhal-Teke incorporates

almost every conventional conformational failing... and, nevertheless,

he is amazingly beautiful and divine, an arrogant equine aristocrat. This

confusion comes from using conventional yardsticks to judge an extremely

unconventional equine.

For a European or American horse expert to assess an Akhal-Teke requires

a conversion. For Russians used to Dons, Orlovs, Kabardins, and an array

of other Russian equine stalwarts, understanding Akhal-Tekes is no problem.

They have admired those “divine horses” for centuries.

The Akhal-Teke’s conformation

is ideal for the environment that produced it.

Body

Its body is tube-like; the breast

is narrow; the back is long; the rib-cage is shallow; the

loin is long and unpronounced. The quarters are narrow, and would

be a nightmare in another horse, but they are spare and sinewy; the

croup is quite long, muscular and with a normal sloping angle.

The withers are high, long and well muscled. The shoulders are

long, with good slope and very clean shoulder bed. The coat is

exceptionally fine and the skin thin, in character with a horse of

desert origins. A feature of the breed is a short, silky tail.

Head and neck

The head is fine and elegant, in harmony

with the body, with wide cheeks. The nose line

is straight or slightly dish-like, and the big eyes give an impression

of boldness. The nostrils are wide, thin and dry, and there is

width between the long, beautifully shaped alert ears. The head

joins the long, lean neck at an angle of 45 degrees. The neck is

set very high and almost vertically to the body. The forelock and

mane are not very long.

The line from the mouth is often higher than the withers, a feature peculiar

to the breed.

Legs and feet

The legs are long, clean and

dense with clearly defined sinews. The forelegs are usually set close

together and are straight; the forearm is long. The hindlegs are

long, the hocks are carried high off the ground. The feet are

small but regular, the heels are set low, the hoofs are small and

hard. Fetlocks have little to no hair.

The Akhal-Teke’s pasterns differ from those of other breeds. In

other breeds the front pasterns are normally a little bit longer and are

positioned a little less vertically than the rear ones. But an

Akhal-Teke’s rear pasterns are not shorter than the front ones, and are

positioned less vertically than the front ones. Probably, it is an unusually

loose surface that made the Akhal-Teke horses develop a specifically shaped

pastern.

Movements

The Akhal-Teke’s movements are unique, like

the horse itself. The way he carries his body, turns his head, shifts

his sensitive ears, rears, etc., is absolutely fascinating.

The Akhal-Tekes are products of the sand desert, and the style of their

pace is ideal for sands. It is specifically “soft and elastic.”

The Akhal-Teke’s desert cousin, the Arabian, comes from a stony desert,

and he usually walks lifting a leg high, with his body shaking.

Though the Akhal-Teke’s pasterns are somewhat more upright, he walks

in a much smoother manner, sort of sliding over the ground in a flowing

movement without swinging the body, which is better balanced. The push

is “elastic” but powerful.

The trot is also free-sliding, and the gallop is easy and long. The jumping

action of the Akhal-Tekes is cat-like.

Temperament and attitude towards humans

The Akhal-Teke horses are vigorous, excitable,

and restless. Thousands of years of selective breeding have left their mark not

only on their physical appearance and efficiency, but also on their behavior.

These horses are not only sensible but also very sensitive; they are even able

to respond to mental suggestions of humans. Their intelligence is not

comparable to any other breed.

They are essentially one-master horses. Some Tekes may be difficult when ridden

by strangers. With them you cannot achieve obedience by shouting or punishment.

A glance, a small gesture, or a soft-spoken word are sufficient. A punishment

not understood by the horse can cause them to be in a defensive mood for weeks.

They are horses with character, outspoken individuals.

Says Sue Waldock, President of the Akhal-Teke Association of GB: “They

respond best to daily love and attention, a bit like a dog. If you ignore a dog

it will misbehave too. Bonding with a human owner is in their

blood.”

They are not suited to nervous or irritable humans. They not only need a sensitive rider, but a human being who can share their feelings when they gallop over vast areas just for the joy of movement. They are not suited to the limitations of modern stables, which kill their spirit. They are horses belonging to wide open spaces.

Colors

Hardly any breed can compare with the

Akhal-Teke in variety of colors, which include chestnut, bay, gray, palomino

(isabella) , raven black, dun. All the colors, except for raven black, are gold

iridescent (the gray ones are silvery). This makes the Akhal-Teke horses very

attractive.

The percentages of colors within the breed according to a survey made in 1978:

black — 11.7%, dark-brown — 1.9%; sorrel — 10%; dun —

17.1%; palomino — 6.1%; and white — 10.2%. Light palominos were

previously excluded from breeding because their eyesight is poorer in glaring

sunshine.

During the past few years a certain shift occurred due to a decrease in

gray-white horses, which was caused by their being more susceptible to

melanoma. As a result of this, there are more bay horses of all shades

now, including perlino and dun. This in turn can be accounted for by the

increased demand for horses with special colors (gold and silver shine),

especially in international markets.

Boinou 1885 The Stock sire of the breed |

Mele Kush 1909 Line founder |

Everdy Telek 1914 Line founder |

Bek-nazar-dor |

Ak Belek 1931 Line founder |

El 1932 Line founder |

History

Among 250 equine breeds known today in the world the Akhal-Teke horse

is universally considered one of the most ancient ones. Many researchers regard

it as the most ancient one. Of ancient noblesse, older than that of the

Arabian or the English Thoroughbred, the Akhal-Teke is a full-blooded horse

that is second to none.

The Akhal-Teke’s origins are lost in the dark of centuries, or even

millennia. Cuneiform texts found in Assyria tell us about horses or, as they

were then called “donkeys from the mountains” from Midis and Urartu.

Tiglatpalasar (1115-1077 B.C.) wrote: “I seized huge herds of horses,

mules, and other cattle from their meadows. I made them pay a tribute of 1200

horses.”

Herodotus provides a description of ten sacred horses in magnificent harness

that were paving the way for the sacred chariot of Akhuramazda in the army of

Xerxes. Those horses were bred in the Nisei plain “between Balkh and

Midis.” They were graceful, had long, thin and flexible necks, large eyes,

clearly shaped heads, thin and strong legs.

Images of the Akhal-Teke horse dated to 9th centuries B.C., or even from the

4th to the 2nd millennia B.C., are found in the territory between the Caucasus

and Luristan.

| A horse from Pazyryk excavation (6th century

B.C.) Reconstructed by Swedish hippologist Bo Furugren |

|

Most interesting archaeological evidence was

unearthed in famous Pazyryk ancient man-made stony hill in Altai (Southern

Siberia). The hill was a burial place of a Scythian chieftain. A permafrost

layer at the foot of the hill had almost perfectly conserved equine remains,

dated at the 6th century B.C. The horses discovered were very close to the

modern Akhal-Teke breed.

|

Skeletons of horses more than 2,500 years old, discovered during archaeological digs at Anau, near Ashgabad, also point to their link with modern-day Akhal-Tekes. Around 1,000 B.C. the Indo-German Bactrian tribe raised horses on the north slopes of Afghanistan that were very similar to the Akhal-Teke horses of today. |

Since ancient times the “heavenly

horses” were a political issue. The Persian emperor Cyrus married

a daughter of King of Medes Astyages to gain access to the Bactrian horses,

which he was unable to secure by force. Alexander the Great, through his

marriage to Roxane, the daughter of a Bactrian king, acquired the fastest

and most gallant horses of his time. It is to them he owed much of his

successes on the battlefield. The Chinese, under Emperor Wu, in 103 B.C.,

even started a war to acquire those horses.

Probe, an emperor of Rome, is known to have been presented with an Akhal-Teke

horse that could cover the distance of 150 kilometers a day for up to

ten days in a row.

The Akhal-Tekes have been valued in Baghdad Caliphate (9-10th centuries

A.D.). The Caliphate’s elite army consisted of mounted Turkmen who

rode Turkmenian thoroughbreds.

Alexander the Great, Darius the Great — the Persian ruler and king

of kings; Genghis Khan, and his rival Dzhelaletdin, a Seljuk Turkmenian

national who forced Genghis Khan to give up an idea of a crusade to India,

the lords of Parpha, Mongolia and Turkey, are all known to have used the

“Godly, heavenly horses” in their military campaigns.

Most emotional records are extant of medieval European visitors of Turkmenistan.

Marco Polo paid tribute to the Turkmenian horse. He wrote that Turkmenistan

was producing excellent large horses that were selling at 200 libras each.

Marco Polo traced the ancestry of Akhal-Tekes to Bucephalos, the legendary

stallion of Alexander the Great. Alexander’s affection for that horse

has a material evidence. At the death of his stallion, Alexander interrupted

his campaign to erect a memorial tomb in his honor, which is still in

existence in Pakistan.

The discovery of a Sea Passage from Europe to India considerably reduced

the importance of the continental “Silk Road.” The Silk Road

crossed Turkmenistan and contributed a lot to interaction of Asiatic peoples.

The peoples settled down along this way, Turkmen included, became “forgotten.”

Since the 17th century the role of the Akhal-Teke horse was mistakenly

assigned to the Arabian breed.

Breeding Practices

|

The present-day Akhal-Teke is

the perfect result of the “survival-of-the-fittest” theory at work

for millennia. They have been exposed to the unparalleled rigors of the

environment and testing uses to which they have been put by their

masters. |

Like Arabs, Turkmen have been guarding the purity of their thoroughbreds for centuries. They helped the Akhal-Teke pass on his nobility through millennia. Professor Vitt, an expert in and the author of books on the Akhal-Teke horses, pointed out that the Akhal-Teke horse managed to preserve in itself “the last drops of the source of thorough blood that generated the world riding horse-breeding.”

It took Turkmen centuries to perfect the breed. The horse has been virtually produced by the humans, to live with the humans, to fight with the humans, and to die with the humans. Turkmen, those denizens of the desert, needed a companion horse that would survive in the red-hot sands, carry a warrior with his weapons and supplies for days on end. The very existence of the Turkmenian tribes was to a large measure dependent on the possession of the superior horses.

A horse has always been the best friend of the Turkman. Each horse was looked upon as the dearest member of the family. Such a treatment allowed the perfect selection of the best individuals for continuous improvement of the breed. The Turkmen have a saying: “After you have visited your father, see your horse.”

The Akhal-Teke horses were never allowed to graze in a free herd. Instead, each horse was individually brought up and taken care of.

However, this did not spoil the horses. On the contrary, skilled seises – trainers helped the horses develop extraordinary stamina and speed. The Akhal-Tekes can stand hunger and heat. They can also do without water longer than other breeds.

Turkmen used to hand feed Akhal-Tekes with a high-protein diet of dry lucerne, pellets of mutton fat, eggs, barley and quatlame, a fried dough cake.

In the 20th century a few English horses have been taken to Turkmenistan “to upgrade” the breed. Fortunately, it was understood quite soon that that could destroy the unique characteristics of the Akhal-Teke horse. The experiment was discontinued. It is safe to say now that the Akhal-Teke is the world’s purest breed.

Saparkhan 1937 fATHERLine founder |

Karlavach 1939 Line founder |

Classical Sports

|

When breeders increased the

size of Akhal-Tekes, they began to be used extensively in classical equestrian

sports. Moreover, statistics shows that in relative terms the Akhal-Tekes have

been the most successful breed in Russian equestrian sports. A household name with all lovers of the breed is the black Absent, the seven-times national champion, the Olympic champion of Rome in 1960, the Bronze medalist of Tokyo in 1964. International journalists dubbed the stallion the Horse of the World. |

Another Akhal-Teke outstanding dressage horse was Abakan, who with Elena Petushkova won the National Championship in 1979 and the USSR Winter Championship. Akhal-Tekes excel in jumping as well. They jump like cats. Absent’s sire Arab jumped 2.12 meters; Poligon jumped 2.25 meters — the record for Akhal-Tekes. A remarkable feat was performed by the Akhal-Teke stallion Perepel in 1950 in Ashgabad, when he did a broad jump of 8.78 meters. The official record acknowledged by FEI stands at 8.26 meters. |

|

The Akhal-Teke has a huge potential in classical sports that should be developed.

The Akhal Teke and Other BreedsThe ancient Turkmenian horse was so much superior to other contemporary breeds, that the horse was very much sought after. The Turkmen did all they could not to allow uncontrolled spread of their treasured steeds. It was not that easy, since Turkmen were taking part in numerous campaigns, not only in Central Asia, but also in Iran, Arabia, Egypt and even Spain. Nevertheless, Turkmen did manage to preserve the superior qualities and beauty of their national horse.

The Akhal-Teke and the Arabian

There is an historical evidence that proves

that the Arabian thoroughbreds appeared much later than the Akhal-Teke ones.

For instance, Herodotus pointed out that warriors of the Arabian origin in the

army of Xerxes used camels, and not horses as a means of transportation. A

cuneiform script dated 733 B.C. says king Taglatfalassar seized in Arabia 30

thousand camels and 20 thousand cattle. Though the operation is described in

much detail, no horses have ever been mentioned.

Even Sardanapal V, who bragged he had collected all treasures of Arabia, did

not say a word about horses. Strabonus who was seeing off the Roman commander

Gallicus to Arabia said: ”Arabia possesses plenty of horned cattle, but

there are no horses, mules, pigs, goats or hens there.”

Only Ammian Martselin, who lived in the second half of the fourth century,

spoke casually about horses, when describing customs and habits of

Saracenians.

Hence, the Arabs were not been using horses in the early centuries of A.D.

Thus, it is safe to assume that it was the

ancient equine breeds of Iran and Central Asia, the noble Turkmenian breed

included, that have contributed to the Arabian breed. So, the broadly accepted

notion of the Arabian breed being the world’s elder, and the Akhal-Teke

horse being its offspring, is not supported by historical data. The body of

historical evidence testifies quite to the opposite.

The Arabian expert C.R. Raswan proves that the high breeding results of the

Turkmenian horses caused the Arab breeders in Iraq to pair their mares of the

Muniqui line with the Akhal-Teke stallions.

The Akhal-Teke and the Thoroughbred

| The English thoroughbred counts besides the Arabian Darley Arabian (1713) and the noble Barb Godolphin Barb (1731) also the Turkmenian Byerly Turk (1689) as their ancestors (the names alone point to their origin). We find still other Turkmenian stallions, such as Darcy Yellow Turk and Darcy White Turk. |  |

During the Protectorate, Oliver Cromwell, who

was ardent lover of horses, purchased Darcy White Turk, recorded as the most

beautiful southeastern horse ever brought to England. Then followed Helmsley

Turk (1675), Acaster Turk, Belgrade Turk (1675), Johnson’s Turk and

Piggot’s Turk, to name but a few.

Later on, Akhal-Tekes continued to influence English and Irish breeding. In

1877 an Akhal-Teke stallion was imported to England and then to Ireland. The

stallion was remembered for his staggering stud fee of 20,000 guineas. He

influenced the development of the Irish Hunter.

The Akhal-Teke and the Trakehner

Outstanding Akhal-Teke Individual horses

reached various countries of Western Europe. Some of them are still remembered.

For instance, a stallion by the name Turkmen-Atti became a founder of a highly

valued and the most widespread line of Trakehners early in the 19th century.

The Turkmen-Atti story is quite indicative of the ways exotic Turkmenian horses

found their way into Europe. In the 1890s he was presented to empress Catherine

the Great. The horse somehow emerged in Austria some time later, allegedly an

Arabian from Damascus. People there were unable to determine his breed. They

brought him to Professor Nauman of Berlin, an unsurpassed equine expert of the

day. The professor studied the horse carefully and proclaimed that the Arabians

were not so tall and they did not have such a golden sheen. It took the

professor some time to find out that the horse was brought to Vienna and Berlin

from Russia.

At a royal reception foreign visitors were treated to a horse show. The unknown

horse caught everybody’s fancy with its elegance and golden color. A

visitor from Turkey exclaimed enthusiastically: “A Turkmenian horse!”

That’s how the mystery was solved and how the horse came to be known as

Turkmen Atti (The Turkmenian horse).

Turkmen Atti, and his numerous offspring, passed their qualities to the

Trakehner thoroughbreds of Germany, the Nonius thoroughbreds of Hungary,

half-breeds of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia.

Karl W. Amman, the manager of the Trakehner farms, strongly suggested in 1834 the utilization of the Akhal-Tekes in a program to ennoble the European warmblood lines. His views were echoed by J. Russel Mannings in 1882: “The Akhal-Teke is, of all breeds, the best suited to improve the warmblood riding horse.”

The Akhal-Teke and Oriental & Russian breeds

The Akhal-Teke thoroughbred significantly

influenced the development of cultured horse-breeding in Iran, Afghanistan,

Pakistan, India, and other counties of the East. Among these are the Karabair,

Lokai, Naiman, Karabach, and Kabardin.

Also, the Akhal-Teke influenced many of Russia’s breeds, such as the Don,

Strelets, and Orlov-Rostopchin

Names of Horses

|

Turkmen use many words and expressions to describe and name horses. These words refer to a horse’s color, markings, and temper. The following are a few examples. |

Turkmenian names of Akhal-Tekes horses often contain information about their colors: the word Mele means dun; Kara, black; Dor, bay; Al, chestnut.

If a horse has an ermine above the hoof, the horse will be called Ak Toinak (White Hoof). If a horse has a white sock, it will be referred to as Ak Bilek (White Forearm).

Turkmen like white markings on their horses’ legs. In olden days they said, one white leg means one denga (local money unit), two white legs mean two dengas, and three white legs mean three dengas. But four white legs are believed to be too much — a suggestion of no money. Quite similarly, Turkmen believe that white stains on the stomach are a poor sign. They have a saying: “A man riding a piebald horse would not conquer a mountain.”

A white star on a horse’s forehead is called Depel. That’s why some horses are called, say, Ghyrdepel (a gray with a star), Dordepel (a bay with a star). Horses with a white muzzle are named Burnak. Turkmen adore that marking.

Inche is the name given to horses with a white stripe. And so, Inchedor means “a black with a stripe”, and Inchegara means “a sorrel with a white stripe.” White-faced horses are called Akmanlai.

Horses with a white tail and a white mane are known as Akial. Akials’ body may be dun or gray. Turkmen believe Russians prefer Akials, especially for circus performances. Turkmen like them, too.

For Turkmen the least favored color is Chakhan, whitish with red eyes – albinos. Red eyes cannot stand bright sunshine. Aksakals (the elders) believe those horses harbor vicious ghosts.

The color most favored by Turkmen in dun with black knees and the tail. The forelock is raven-black. If you take a good look at the head, you could see some tiny eyebrow-like stripes above big black eyes. Thin ears have black fringes. A marvelous combination of colors!

Purely gray horses are believed to be beautiful as well. When adorned with national Turkmenian silver decorations, gray horses look stunning.

It is not only colors and markings that are reflected in Akhal-Tekes’ names. Turkmen like to compare their mounts to birds, hence one finds the word Kush so often in horse names. For instance, Mele Kush means a dun bird.

Skak 1940 Line founder |

Fakirpelvan 1951 Line founder |

Endurance

Tarlan Winner of a multi-breed five-day ride in 1945 |

The Akhal-Tekes are horses of extraordinary endurance. They were referred to as “greyhounds among horses” (R.S. Summerhays). Endurance was developed by the most rigorous natural selection in raids and wars, in which thousands of horses died, and only the toughest survived to pass on their phenomenal qualities to their progeny. Stamina was also achieved by fairly unusual methods of training and preparation. |

Fraser writes about this: “The endurance of these horses is indeed incredible. When Turkmen start on one of their plundering raids the horses are not only burdened with the riders' weight, but have to carry a supply of provisions as well; and despite of that, they cover 80-100 English miles in 24 hours, and often can do this for several days in a row. When Turkmen plan to make a raid requiring strong effort and speed, they make their horses run a distance of many miles daily, feed them sparsely with barley and wrap them up with blankets during the night. They continue to do this until all superfluous fat disappears and their muscles become hard as marble. They check the desired condition of the flesh by examining the neck muscles and thighs. After thus being prepared, the horse attains incredible speed and endurance, and he will run almost as long as his rider demands without losing strength or getting tired. Horses which are well nourished before starting on such a sortie seldom can withstand exertion of such kind.”

Muraviov in his book Travels Through Turmenistan and China (1820) wrote: “It is hard to imagine what these horses can endure, in eight days they cover about 143 German miles through waterless, bare deserts, eating only small quantities of Gogan (millet) and sometimes going without water for four days in a row.

In the 1880s when the Russians came to Turkmenistan they were amazed by the performance of the Akhal-Tekes. Colonel Artsyshevsky wrote in the Magazine of Horse Breeding (1882, No 2): “I had at times to cover 160 kilometers a day switching horses, whereas the Turkmenian jighits who accompanied us were riding on their horses, and were even sent out on outriding and scouting missions. In addition to the rider and the saddle, the horses carried at all times huge felt coats and various supplies.”

Major Spolatbog in the same magazine (1881, No 12) recounts an episode of the Gheok-Tepin battle: “An Akhal-Teke stallion with three Teke warriors and two heavy felt coats aboard and wounded by a saber escaped the pursuit of Cossacks over shifting sands and reached Merv (500 km away).”

|

The

Winged Soul In 1935 Akhal-Teke and Iomud horses completed a ride from Ashgabad to Moscow, a distance of 4,300 km, in 84 days. It included some 360 km of desert, much of it crossed virtually without water. This feat has never been equaled. The Turkmen have a saying: “If the carpet is the Turkman’s soul, the horse is his wings.” This “horsey” carpet was made to commemorate the 1935 ride. It is a winged soul! (There is a video documenting that ride.) |

In 1945 a 500-km endurance race in Moscow of eight breeds was won by the Akhal-Teke Tarlan. Further rides were in 1983 and 1988, and again Akhal-Tekes were winners.

A Turkmenian team will take part in the Nissan World Equestrian Games at Punchestown, Ireland. They have high hopes of winning the 160 km, eight-hour endurance event

Peren 1955 Peren line founder |

Gelishikli Line founder |

Kaplan 1957 Line founder |

Polotli 1965 Son of Peren |

Folklore

| Since times out of mind the

Turkmenian and their horses have been inseparable. And it is only natural that

in a nation that has been so much dependent on its horses there would be many

legends and songs about mutual devotion of people and horses. The Akhal-Tekes

are invariable personages of Turkmenian fairy tales and parables. The horse by the name of Gyr-at (Gray horse) is the main hero of the famous Turkmenian saga Kerogly, or “Gherogly.” Fact and fable blur into one as people recount the proud past of one of the world’s most noble breeds. |

|

Here is one legend:

One horse was invincible in a traditional race. The elders then ruled that this

horse should compete with a falcon. Thousands of people came to watch the

contest.

The horse swung into gallop the moment the falcon started its flight. And the

horse won. Since then people give birds' names to horses, such as Melekush,

Garaggush, Lachyn, Durna, Burgut, etc.

Turkmen have many beliefs and superstitions concerned with horses. Hence the trappings of their horses may include many exotic omens and charms.

Pedigrees

Turkmenian like to be aware of the ancestry

of both people and horses. So, when two men meet for the first time they

greet each other this way: “What’s your clan?” or “Whom

do you belong to?” Much like the Arabs, the Turkmen had no written

records of their horses’ pedigrees. But the masculine line has always

been remembered. Fathers used to pass this data on to their sons in story-telling.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that every Turkman knows the names

of the best Turkmenian thoroughbreds and sires.

Nowadays, any Turkman, even though he is not involved in breeding or training,

let alone professional seis (trainers), would recite the lineage

of celebrity stallions in detail.

Turkmen have traditionally valued superior horses. That is why they used

to take their mares to extraordinary stallions, no matter how long the

distance was.

The owner of Bek-Nazar-Dor, the stock sire of a line that is still highly

valued, was riding his Akhal-Teke stallion between settlements during

the breeding season.

Now the data on all stallions and broodmares is recorded in properly kept

stud books. The data is based on verified archives, and inquiries among

horse-breeders.

Documenting the breed begins only since 1885, the year of the birth of

Boinou by Lelyaning Chepi, Karamchi’s grandson, Kutly Sakar’s

great grandson — just so generations could remember the illiterate

Turkmen.

The first proper study of the breed was conducted in 1927 by an expedition

headed by K. Gorelov, to whom goes much of credit for the analysis of

word-of-mouth pedigrees and the construction of the genealogical structure

of the breed.

His findings, supplemented by further studies, laid the foundation for

the State Stud Book of Central Asian Equine Breeds published

in 1941. It contained information about 287 stallions and 468 mares of

Akhal-Teke origin.

|

All the information and photographs for this section were kindly provided by Troika, the ultimate Russian horse resource online. For further information on Russian horses and horsemanship please click here |

The Akhal-Teke Society of Great Britain

Asphodel Rock Wadebridge Cornwall, PL27 6NW

Great Britain

Tel. +44 (0) 1208 862226

Fax: +44 (0) 1208 862226

Contact person: Sue Waldock e-mail: SWALDOCK@compuserve.com